A Sermon for Bloomsbury Central Baptist Church

8 December 2019

Isaiah 40.1-11

Mark 1.1-4

Luke 4.14-21

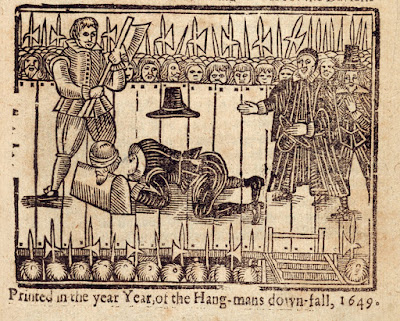

In the middle decades of the seventeenth century, nearly 400

years ago,

it must

have seemed as if English society was being turned upside down,

as this famous picture from the mid-1640s depicts:

with a cat

chasing a dog, a rabbit chasing a fox,

a

cart before a horse, an upside down church,

fish

swimming in the sky,

a candle

burning the wrong way up,

a

wheelbarrow pushing a man,

and

gentleman who clearly got dressed in the dark.

So what caused such upset?

Well, to start with, there were the political ramifications

of the civil wars,

with

Cromwell and his armies trying, and eventually succeeding,

in their attempts to overthrow the

monarchy

and reform the entire mechanisms of

government.

But the political and constitutional crisis was just one

half of the story,

because the

execution of the king was a theological

crisis as well.

At this point society was only a hundred or so years on

from Henry

VIII’s infamous break with Rome,

and his setting up of a national state Church of England,

with himself

and his heirs as its head, in place of the Pope in Rome.

So, when we get to the seventeenth century,

the

regicide of King Charles at the hands of Cromwell and his armies,

was

an event that struck a blow

at

the roots of all the dominant structures of English society.

Suddenly, the national Church of England itself was under

threat,

and this

created the context in which rebellion could flourish,

with breakaway groups such as the Quakers and Baptists

refusing to

pay their tithes or baptise their babies,

and other even more radical groups such as the Levellers and

the Diggers

arguing on

religious grounds that the wealth of the country

should be

redistributed for the benefit of the poor.

And I want us to pause for a moment here,

because I

find the Levellers particularly interesting;

not least because of their links

to the

early pioneers of our own, Baptist, tradition.

Unlike the more anarchist Diggers,

the

Levellers were not arguing for some proto-Communist ideology,

where the

rich are thrown down and the poor raised up.[1]

Rather, the Levellers took a more nuanced and

creation-centred approach.

They argued

that the land itself was a gift from God,

given for the benefit of all those live upon it.

And so their issue was not that some were wealthy and some poor;

rather it

was that the land,

the

fields and the forests of England,

belonged to

neither the rich nor the poor.

The land of England, according to the Levellers, was God’s

territory;

and the

humans who lived on it, whether royalty or peasant,

did so only

as God’s tenants.

So the Levellers took particular issue with the enclosure of

the common land,

and argued

for the right of each person

to be able

to make a living from the soil.

The Levellers also argued for greater democracy,

believing

that all humans are worthy of a say in the running of society;

they argued for greater religious tolerance and freedom;

and for the

equality of all before the law.

The movement only flourished for a few years,

in the mid-

to late- 1640s,

but for that time they were hugely popular,

reaching

many people through their extensive pamphleteering.

But they were also, as you can imagine,

hugely

controversial with the powers that be.

Although many in Cromwell’s army were sympathetic to the

Levellers,

he himself

was rather more sceptical,

and there’s a memorial in Burford in the Cotswolds

to three

Levellers shot on Cromwell’s command.

They weren’t a political party in the modern sense of the

term;

so you

couldn’t vote for them in an election, for example,

not least because they didn’t have

elections

as

we know them in the seventeenth century!

But nonetheless they were a populist political and religious

movement,

seeking to

change the face of society

in the

direction of social justice.

But here’s the thing, as we gather on the Sunday before

an election…

on many of

the issues they took a stand on,

I

confess I find myself in considerable sympathy with them:

I do

believe each person has the right to make a living,

the

right to vote, the right to believe as they choose,

and

the right to be judged impartially by the law.

I’m in

favour of religious tolerance,

and

of the innate value of each human before God.

Back in the seventeenth century, the Levellers of London,

many of

them members of a Baptist church over in the City,

mounted a

campaign, with petitions and actions,

to present to their civic leaders,

in the hope

that their cause would be heard,

and changes

could be brought about

to

benefit the poor and curb the excesses of the rich,

without the

need for wholesale revolution.

In the end of course, as we know, the Levellers didn’t

succeed;

revolution

came, armies were mobilised,

a king lost

his head, and a nation fought for its identity.

But I like to think their spirit still lives on.

In many ways,

the

challenge of those turbulent years from four centuries ago,

still rings

down to us today.

I’m not sure that those early Baptist Levellers were all

that different to us,

as we put pressure on the political powers of our time

to make the city a more just place for all to live,

joining with other churches, mosques,

to make the city a more just place for all to live,

joining with other churches, mosques,

synagogues

and educational establishments

through

the work of London Citizens.

So don’t forget to put Tuesday 21st April in your

diary,

to join

with the others from Bloomsbury

at the

Copperbox in the Olympic Park

to engage

the 2020 London mayoral candidates

on

issues of youth violence, homelessness,

climate

change, fair employment, and the like.

The fundamental issues that inspired the Levellers

to organise

their members for a better society

are still

issues that inspire people to do the same today.

And the cost of failure still remains just as high:

if these

things are not addressed,

then even

more people will die on the streets of our city.

It matters deeply to us, just as it did 400 years ago,

that

society is just, fair, equal, and impartial.

And here’s the thing;

another lesson we can learn from the activism of the Levellers:

it is the responsibility of each of us

another lesson we can learn from the activism of the Levellers:

it is the responsibility of each of us

to make

every effort to bring a better society into being.

And we do this, not just out of self-interest,

although

that should not be underestimated.

But rather, as Christians, we do this

because be

we believe it is in the interest of God.

The passage we had earlier from the book of Isaiah

speaks of

every valley being lifted up,

and

every mountain and hill being made low;

it speaks

of uneven ground becoming level,

and

of rough places becoming a plain.

It is a vision of the levelling of society,

of the

evening out of those areas

where

people are laid too low, or raised too high,

of the removal

of the obstacles to inclusion and participation

that

cause people to trip and stumble.

It is a

vision of the in-breaking kingdom of God,

and

it tells us that this process is the mechanism

by

which the glory of God is made known amongst people.

This morning's passage from Isaiah was written towards the end of the

exile in Babylon.

And if you

were here last week,

you

may remember that we were hearing from the Prophet Jeremiah,

who

predicted the start of the exile

and

the downfall of Jerusalem to the Babylonian army,

and yet

offered words of hope

to

people living in the midst of despair.

Well, chapter 40 of Isaiah comes from a few decades later,

when

Jerusalem has indeed been destroyed

and

the people carried off into exile;

but the

message of hope is still there.

Isaiah prophesies a return to Jerusalem,

and he

offers the exiles words of comfort.

He says that the punishment for the people’s sin,

foretold by

Jeremiah and enacted in the exile,

is nearly at an end,

and that the

restoration of Israel is at hand.

And I want us to pause for just a moment here,

to consider

the theological implications

of this

idea of the exile being a punishment on Israel for unfaithfulness.

This assertion that a people group, in this case Judah,

bear the

consequences of their leaders’ sinful decisions

can seem a deeply troublesome concept:

after all,

why would God punish the ordinary people

by

sending them into exile,

just

because their king took decisions

that

were displeasing to God?

Except, of course - this happens all the time, everywhere.

The people

always pay the price for the bad decisions of their leaders.

And I wonder if the way to look at this

is to

recognise that terrible leadership

can lead to

terrible suffering,

and this is true whether we live in ancient Israel,

or 21st Century London.

and this is true whether we live in ancient Israel,

or 21st Century London.

It’s not as if God hadn’t warned Israel!

In the

first book of Samuel,

when

the people cried for a king in place of judges to rule them,

Samuel had

told them in no uncertain terms

of

the price they would eventually have to pay

for having a King like the other

nations (1Sam 8.10-18).

But no, they said, they still wanted a king

to lead

them and fight their battles.

In our days of more enlightened democracy,

we might

say that people get the leaders they vote for

- but even

here that’s not always true.

Many a prime minister has been elected to office

with far

less than a majority of the population having voted for them.

And it is so often the disenfranchised, the impoverished,

and the vulnerable

who pay the

price for bad decisions taken

by even their

most democratically of elected leaders.

It is a fair certainty that by this time next week,

some of us

are going to be disappointed in the election result

-

whichever way it goes!

And in the midst of this,

perhaps we

will need to hear again the wisdom of Isaiah,

who

proclaimed that nothing lasts for ever.

Even the punishment of Babylonian exile came to an end

eventually.

Isaiah proclaimed that those who are lost will come home again,

Isaiah proclaimed that those who are lost will come home again,

and those

who mourn will be comforted.

Injustice does not get to win forever,

because God’s

kingdom of justice and righteousness

is forever breaking into this world

through the

faithful witness of the people of God

to the faithfulness of God.

Martin Luther King famously said that,

"The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice".

Martin Luther King famously said that,

"The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice".

The comfort proclaimed by Isaiah to the exiles in Babylon

was no

shallow Pollyanna-ish message of hope.

Rather, it was a comfort based on the faithfulness of God.

Because

even if God’s people are unfaithful to God,

God remains

Faithful to them.

And so Isaiah calls for a way to be made straight in the

desert,

for God to

come to his people once again.

He calls for the mountains to be laid low,

and the

valleys to be lifted up.

The obstacles that stand between God and people

will not

last forever,

and God will come again to the world

to bring the

good news

of a

renewed and restored relationship.

There is a personal challenge here for each of us, too,

to consider

what the barriers are in our lives

that stand

in the way of God coming to us.

What needs levelling in us to allow Christ to come to us?

The

capacity for sin to quietly build up until it obscures God from our view

is

something that each of us needs to guard against.

But there is good news in Isaiah too for those of us who feel

far from God,

which is

that we are like sheep cared for by a good shepherd.

Isaiah portrays God as always at work, seeking those who are lost,

and carrying

us gently and safely home,

lifting us up when we

feel too weak to take another step under our own energy.

I think that there is an eternal truth here,

which is

that we are never abandoned,

because God is the Good Shepherd,

and it is

God who satisfies our deep hunger

to be deeply known and deeply loved.

And so we come to the proclamation of John the Baptist in the wilderness,

which was that

Jesus came to bring forgiveness for sins,

to open the

path for God to come to us.

And that message of forgiveness and reconciliation

is as much for

us gathered here today

as it was

for those in the Judean wilderness,

waiting for their messiah to come, two thousand years ago.

waiting for their messiah to come, two thousand years ago.

Just as Isaiah’s message of comfort

is as much

for us

as it was

for those in exile in Babylon, some 600 years before that.

God comes to us,

with good

news, with forgiveness,

with

justice, with comfort, and with reconciliation.

And so we gather in Advent,

to prepare

ourselves for the revelation of God in Jesus,

and we do well to hear the challenge once again:

that God is

discovered in our lives and in our society

when

injustices are undone.

In Christ, God comes to us;

yes, as the

infant in the manger,

but also again and again, God keeps coming to his people and

his world,

by the

Spirit of Christ at work in our midst and in our lives.

According to Luke’s gospel,

at the

beginning of his ministry in Nazareth,

Jesus also

quoted from the book of Isaiah,

Luke 4.18-19

18 "The Spirit of the Lord is

upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent

me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to

let the oppressed go free,

19 to proclaim the year of the

Lord's favour."

The call to become involved in the levelling of society

runs like a

thread through both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament,

I could have pointed us to the sermon on the Mount, or the

Magnificat,

or to countless

other places that speak of justice and reconciliation.

And it challenges each of us to take the faith that we have

in God,

who comes to

us in Jesus Christ,

and to turn that faith outwards to the world,

to have

faith in a new world

that comes into being as we live and pray it into existence.

The vision here is of a world where wrongs are righted,

a world where

the poor receive good news,

a world where those captive

to forces

beyond their control find release,

a world where those blinded to the humanity of the other

are able to

see clearly for the first time in their lives,

a world where those oppressed by ideologies of hatred

are finally

released to love someone other than themselves,

a world where those who are despised by all

find

themselves the object of God’s favour.

This is the levelling we long for,

this is the

levelling that brings life and does not take it,

this is the levelling of the coming kingdom of God for which

we pray and long,

and it is

before us, as it is before every generation.

And it begs of us a response.

If God

comes to us in Christ,

what earthly difference does that

make

to the way we live today, tomorrow,

this week?

And that is a question to take away and ponder,

as we look for

the one who is coming,

and pray for the coming kingdom of God,

on earth,

as it is in heaven.

[1]

Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down, 119

No comments:

Post a Comment